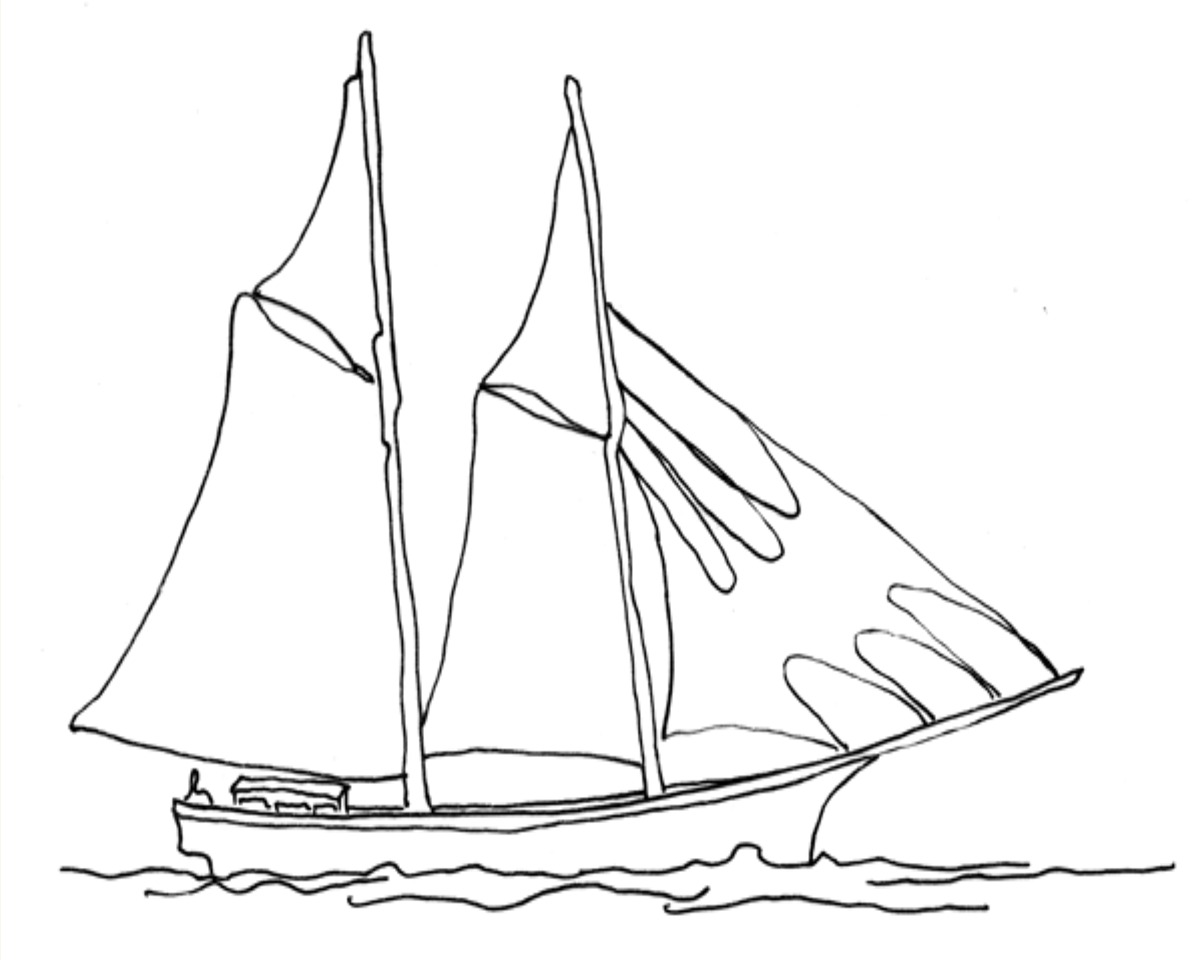

Clinging to the edge of the great gray expanse of Lake Erie, the little two-masted schooner bobbed up and down as Ruth shuffled sideways across the narrow gangplank. Although the gangplank was barely wide enough for one person, she had watched sailors run confidently over the swaying board from dock to ship. Ruth doubted whether she would make it across without disaster. Leading the way, Cordelia tugged eagerly at Ruth’s hand while Gran hung back, clutching at Ruth’s other arm. Pulled between them, Ruth teetered along the plank, trying not to look down at the choppy water below.

Uncle Joe came to the edge of the ship, reaching out to help them across. Finally stepping safely on the wooden deck, Ruth glanced behind her. Her brothers were still on the pier with Mother, hearing last minute instructions from Daidí. In the rush to board, Ruth had missed bidding Daidí farewell, and now, burdened with baggage, a little sister, and Gran, she couldn’t even lift a hand to wave. Daidí usually saved an extra smile for her, which made being the middle and most ordinary child more bearable, but apparently he’d forgotten in all the bustle. Ruth bit back her disappointment and guided her charges away from the gangplank and through the crowd of passengers.

Cordelia clamored to look about, but with an eye on the threatening clouds overhead, Gran insisted on making for the cabin. Ruth patiently shushed the six-year-old’s protests. Seeing to Gran’s comfort was Ruth’s responsibility now that Sally Ann was married and had her own family to look after.

“You’ll have all the way from Ohio to Illinois to explore the Telegraph,” Ruth assured Cordelia.

Looking back to the dock one last time, Ruth saw Sally Ann wiping away tears with the tail of the baby’s blanket as her husband Henry kissed them both goodbye. Staying behind to drive the cattle overland, Henry and Daidí planned to meet up with the ship at Fort Dearborn. That left teenaged Ned as the man of the family during the voyage, but calling Ned a man always made Ruth giggle since he was only a few years older than her. Even now, she could hear his self-important voice upraised as he ordered their younger brother Amos on board.

As Ruth neared the cabin with Gran and Cordelia in tow, two small bodies tumbled out of the doorway. Aunt Betsy followed wearing her usual merry grin.

“Why, there you are!” she exclaimed. “I’ve got a lovely seat all ready for you, Granny Naper! Be a love and watch the boys a moment, will you, Ruth? Then I can get Gran settled. Give me your sack, Gran, and watch your step there.”

The little boys and Cordelia hugged each other, bouncing up and down, as if they hadn’t seen each other nearly every day of their lives. Ruth let her bags and baskets slip to the deck and stretched her sore muscles. A gust of wind knocked her bonnet back, the ribbon catching at her throat. She turned to see if the others had come aboard yet. Yes, there they were, gingerly stepping across the gangplank: Mother, then both boys, and behind them, arms loaded with parcels, was—

“Daidí!” Ruth grabbed the children and gave them a little shake. “Stay right here! Stay with the luggage!” She squirmed through the crowd to where her father was handing his packages over to Uncle Joe. He turned and hugged her hard. “I couldn’t let the ship sail off without saying goodbye to my wee Cailín.

“No tears, now. Your mother and sisters will be needing your help more than ever. But they’re the lucky ones!” He smiled and chucked her under the chin. “I’ll have no one to tell the old tales to until we meet again in Fort Dearborn. Henry and the oxen won’t listen as they ought, and they never laugh in the right places like my wee Cailín does!”

Two sailors started to drag the gangplank back onto the deck. Uncle Joe clapped Daidí on the back. “You’d best be off, John!” As quick as a sailor, Daidí climbed over the rail and leaped to the dock. The anchor was raised and as the ship slowly pulled away, Daidí took off his hat and waved it overhead. Mother didn’t wave, but she blinked as if her eyes stung. Sally Ann wailed as loud as the baby she clutched against her chest, and Mother spoke to her in a low voice that Ruth only barely heard.

“You don’t want your husband to remember you like this. Smile for him! It’s the last he’ll see of you for weeks.” Sally hiccupped and straightened her shoulders, smiling so brightly that Henry would be sure to see her over the widening gap between the ship and shore.

Everyone jostled to get a last look at their little town of Ashtabula. Ruth suddenly remembered she had left Cordelia and the Naper boys by the cabin, and threaded her way back. They were no longer jumping, but huddled together solemnly in the forest of trousers and gowns. Ruth lifted Cordelia up for a last look. “Say ‘farewell’ to Ohio, Cordelia! We’re off to a new home in Illinois.” Cordelia waved as the two little boys pulled at Ruth’s skirt, demanding to see, too.

Aunt Betsy joined them, hoisting a boy up on each hip. “So, we’re on our way! Gran didn’t want to come up to see us cast off. She said her goodbyes yesterday.” Ruth nodded, remembering how they had stopped at the cemetery where the grass was only just beginning to cover the bare earth of Grandfather’s grave. She could almost see the cemetery from here, high atop one of the green and overgrown bluffs that loomed over the harbor village.

As the familiar shore slipped away behind them, Ruth suddenly had a vision of Maimeó and Daideó, her Murray grandparents, standing just like this at the rail of another ship as Ireland faded into the distance. Ruth heard sniffling in the crowd behind her and felt an answering lump rise in her throat. In this year of 1831 dear Ashtabula finally felt civilized, like a community instead of a fur-traders’ camp. Now they would be starting all over again.